The History

The history of Huangbaiyu begins all the way back in 2002 at the first meeting of the China-US Center for Sustainable Development (CUCSD), an organization co-founded by William McDonough, the renowned sustainability guru, architect, and co-author of Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. Over the next two years, McDonough and his team hammered out a way to bring the concept of sustainable cities to China, a process that culminated with a 2004 agreement and 2005 announcement of the Huangbaiyu Model Eco-Village [1, 2]. The announcement came at a time similar to that of Arup and SIIC announcing the Dongtan project with the effect of creating an international fervor over the sustainable projects launching in the Middle Kingdom. As bloggers and reporters rushed to locate the tiny village outside of Benxi city in Liaoning province, others heralded the coming of China’s ecological age and extolled the glorious race between two sustainability powerhouses—Arup and McDonough+Partners—to create the first sustainable city. Hope was high that no matter who won, China and the world would win too.

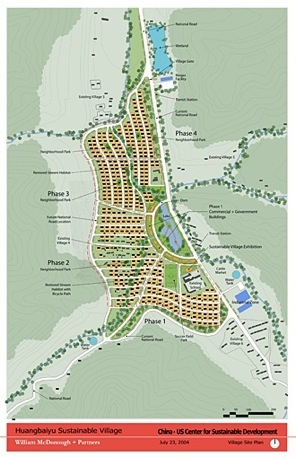

The project was to be the first of 12 cities McDonough would design for China, all built on his trademarked idea of Cradle to Cradle and backed by Deng Nan, the daughter of Deng Xiaopeng, the architect of China’s modern economy. The challenge, as McDonough stated, was to design places for 400 million Chinese to live as they moved to the city without further damaging the economy or ecology. He claimed that if all of those houses were made of brick, China would use all of its soil and all of its coal and be left with nothing for the people to eat and nowhere to get electricity. Therefore, in this first pilot project, McDonough threw off the shackles of the typical Chinese rubber stamp grid with industry as the cornerstone of a new city. Instead, he and his team considered every aspect of the site, looking at wind directions, solar angles, the terrain, agricultural production, and nearby water sources [3]. After several years of designing and consulting, in October 2004, McDonough+Partners released the Village Master Plan to the public. It showed a network of streets and rows of 400 houses winding around a lake and public space as seen in the image below.

In keeping with the Cradle to Cradle philosophy, the buildings were intended to be constructed of locally sourced, rapidly renewable materials that could be easily reused or degraded if the houses were taken down. Agricultural and human wastes were to power and heat the buildings, complemented by solar energy through photovoltaics and solar water heaters. Centralized living was to maximize the agricultural land available to residents, contrary to the current village plans of Huangbaiyu which features multiple clusters of houses spread out by agricultural fields. Finally, all materials were to be audited for compliance with McDonough’s Cradle to Cradle philosophy [1]. To this end, the houses were to be made of locally sourced pressed-earth bricks, and in the spirit of economic sustainability, were not to cost more than $3,500 US—a price deemed affordable for a villager. On top of this, thick walls would obviate the need for insulation and reduce the need for heating. Describing these innovations and his Cradle to Cradle development, McDonough said, “We are doing everything with nothing” [4].

When the plan was brought before the village council for ratification, the residents added a few more stipulations of their own. They demanded that industry be arranged to enter the town and provide jobs. They viewed this as acceptable if they were asked to centralize in the manner planned by McDonough [5].

2005 saw the official launch of Huangbaiyu and the placement of a ceremonial stone at the entrance to the site inscribed with the Chinese characters for the village name facing the road and “HBY” scrawled on the back side [1].

The rock was placed by Dai Xiaolong who was the chief investor in the project and the owner of an alcohol factory nearby. Mr. Dai was set to oversee the construction of the town and help provide the needed jobs by courting American investors through the CUCSD. To the astonishment of the villagers, the ceremony was attended by several dignitaries and political officials from the province [1].

By July 2005, the first phase of houses was well underway, but the project was already facing significant challenges. The cost had risen significantly from the projected $3,500 to between $10,000 and $12,500. As Shannon May, an anthropologist who lived in the village during the process, notes, this value is about twelve times the median household income in Huangbaiyu [5]. Moreover, only one house was fitted with photovoltaic panels—a demonstration house used to show off the project to potential investors and dignitaries who came to visit the site. The cost of this unit, had the panels not been donated would have been $28,000 just for the roof and photovoltaics. Due to the remote nature of the project and the fact that it was one house, the panels were not even connected to the grid [5].

As phase one drew to a close and the first 42 homes were built, work began on the central gasification plant. The homes, with the exception of one granted by the Village Council to a man and wife whose own home had burned, sat empty. Due to cost overruns and mismanagement of construction and funds, the pressed earth bricks McDonough envisioned were produced in an unsafe manner and only the demonstration house had solar panels. The new gasification plant was built slowly until work stopped in 2007 with the main structures and piping laid but without a complete, functional unit. According to one article, the reason for the stop in construction and the abandonment of the homes was that Dai Xiaolong, the entrepreneurial financier of the project, had little construction experience and had thus squandered or mismanaged the project [6].

The Current State

Wander the village of Huangbaiyu and you will find it much the same as it was in 2007 when I ended the history. 42 houses of yellow brick and concrete stand abandoned save for one which is visibly occupied.

I toured the village with Dian Yu, my friend and translator, on a crisp Saturday morning in October and in this supposedly model village, not a soul could be found. As Shannon May wrote me in an e-mail, Dai Xiaolong backed out of the project a couple of years back when he went bankrupt and could not recoup his return on investment and now has disappeared from the scene under allegations of mismanaging funds [7]. When asked about him, several residents indicated that they knew not of where he was, only that he was no longer in Huangbaiyu. The model homes were purchased by a mining development company which some residents said was exploring potential mining in the region and could house workers in the homes; others knew nothing of what the new company wanted with this remote agricultural hamlet [8]. A building that seems as though it would have housed a community center stands empty, the flooring not even finished, while the biogasification unit sits quietly in its half-complete state, looking eerily like a relic from a nuclear war as its yellow and black hazard-like sign and art deco “HBY” look down over the eco-village that never was.

Wandering inside its building, one instantly knows that it at least is performing some of its intended function—it houses the waste of cattle or donkeys who either pass by or belong to the one resident of the model village. Moving back to the houses, on closer inspection one finds that the new structures are already deteriorating under lack of care and in some cases misuse. Rusting gates, broken windows, and dangling pieces of weatherstripping reveal poor construction and neglect of the homes. A peek inside the window and you see empty rooms.

As if an omen of the future of the model village and its tumultuous past, all references to the site have been scrubbed from McDonough’s website and that of the China-US Center for Sustainable Development. Intended to be the flagship of a series of 12 such projects, the only one that remains is the Liuzhou project McDonough touted in his TED Talk as a concept only [3, 9]. Even a reference I managed to find on his site last year when writing my Watson Fellowship proposal which called the project (in paraphrased terms) a good effort and a learning experience for the firm, seems no longer to reside on the website. What once was a featured project for the company now is an unmentionable item. The CUCSD website still lists development of new towns as one of its priorities, but does not refer to the name Huangbaiyu anywhere [10]. It is as if the name of the town is now poisoned.

Walk past the model village up the road into some of the clusters of homes that make up the old village of Huangbaiyu, and you will find the same quiet but thriving village that was present before McDonough and the CUCSD stepped into the picture. On arrival it’s rather hard to believe that this is the village—at any one time you can only see one or two small streets of houses and their residents, but the picture becomes clearer when a resident explains the layout of the 9 clusters of homes and the scattered fields and houses between. Then as you walk, you can see that even on a Saturday morning, farmers were out tending their fields, some harvesting already, others feeding chickens and ducks or watering, hoeing, or tending to other tasks.

Reactions

In the early part of the last decade, when the project was in development and early stages of construction, optimism abounded for green cities to provide a solution to many environmental and developmental challenges. The world political stage was set for China to make a big move in this field and push the US and other laggards into adoption of more environmental policies. After all, many of the failures to achieve strong international climate change legislation revolved around the fight over responsibility between the US and China. Huangbaiyu was caught up in this optimism. With its renowned architect and strong political support in China, bloggers and reporters overflowed with praise and hope for the project, hailing it as the first city in a new wave of ecological development for China and the world [11, 12, 13]. Even as the project was built and the mounting costs spelled doom for the project, the indicators were only visible to those most closely acquainted with the city.

Looking back at the dates on articles about Huangbaiyu, it wasn’t until 2007, nearly two years after the first 42 houses were completed and left empty, that attitudes about the “Model Village” began to change. By this time, Stage three was supposed to have been well underway with the final buildout in preparation for opening in tandem with the Beijing “Green” Olympics. A significant part of the reversal in press coverage came from the comments of Shannon May, the aforementioned anthropologist who lived in the village and watched the project fall apart firsthand. As she says on her website, she broke her silence out of frustration at seeing continuous support for the Model Village from foreign reporters who knew nothing of the actual site and conditions [1]. Shannon’s comments subsequently appeared in several articles and even a documentary which took a closer look at Huangbaiyu, peeled back the shiny yellow paint, and revealed the greenwash underneath [14, 15, 16]. In 2008 and beyond, Huangbaiyu slowly faded from the consciousness of bloggers and reporters, along with Dongtan, as many turned away from the lost hopes of China’s eco-cities to the promise of a desert dream in Abu Dhabi’s Masdar City. On my visit to the village, the bus driver who has worked the route since before the project began, said that he used to have a lot of white people riding to and from the village, mostly under Shannon’s guidance. Now, he said, I was the first he had seen in a while, perhaps since the last time Shannon visited [8].

Yet though interest from international commentators and reporters dwindled, that didn’t change the fact that 42 yellow houses still stood in a small village in China. Perhaps more important than the reactions of the international community then were those of the people who were supposed to be served by the new development—those who walked by them day after day, a constant reminder of the village that never was. Did the end of construction cause a deflation of their hopes for a new village too?

A few reporters ventured into the village in their investigations of the project and along with Shannon’s observations from her 18 months living there provide some insight into the thoughts of the residents. One resident, commenting to McKenzie Funk of Popular Science, perhaps summarized the views of the residents succinctly when he said, “This project is a waste of money. These houses are suitable for factory workers, not country people” [6]. I suggest that this summarizes the general sentiment because if you recall, one of the stipulations imposed by the Village Council was that if the villagers were to be asked to move into the new houses, they required industry and jobs to be brought as well. As Shannon explains, the houses were not fit for those who relied on agriculture for their livelihood. To her, residents expressed concern over the inadequate space the yards allotted for selling and storing maize, goats, fish, or silkworms. Others said that the distance from the hills and river would make it harder to earn the money they needed to live, let alone pay for the new houses [1].

Some of my own observations from a trip to the village corroborate the words and sentiments expressed in these statements. Walking through the model village, it was easy to spot the one occupied house near the back of the development right up against the hill by the smoke issuing from its chimney. Passing by the front, the yard overflows with corn stalks, both harvested and growing, chicken coops, and farm tools. It is easy to see that the yard is insufficiently large for the residents to make their living as they have expanded into the abandoned yards of the neighboring houses to ensure their livelihood.

This is compared to the expansive fields of the farmers up the road which stretch across so much land that it is easy to believe when traveling between clusters in the Huangbaiyu village that you have left civilization entirely.

Walking through the village, my companion and I were met by several farmers out and about and with whom we could stop and chat. Many were eager to inquire if I was a friend of Shannon May—because of their long friendship with her and my white skin, I was instantly associated and was happy that following a few e-mail conversations with Shannon I could respond of her and her family’s good health. When asked about the model village, two of the villagers we chatted with told us straight that no one wanted to live in the houses. One man said that they were too far from their homes, too expensive, and people were happy where they were. Another who lived in the farthest cluster from the model village, said simply that they were no good [8].

Interestingly, my companion and I also met with some very different responses. After stopping and chatting a while with a group of men taking a break from their work in the fields, we slowly turned the conversation to the Model Village. One man, the spokesperson for the group, said that the houses were good, the project was good, and the only reason no one lived there was that everyone wanted to but because only 42 existed, not everyone could. Therefore, to be fair to everyone, no one lived in there. As he spoke, his three companions sidled away, whispering among themselves. My translator and friend told me later she thought he was just repeating rhetoric he had heard from the elsewhere so that the leaders who signed off on the project might not lose face. She thought that because we were knew and not yet trusted friends, he was not giving us his true opinion and that is why his friends moved away, dissociating themselves with the false opinion. A similar sentiment, however, was expressed by a group of children we met on the road. After playing with the kids for a few minutes, , through a translator answering all of their questions about my appearance, and letting them prove to themselves that the hair and beard were real, we asked them about the new houses. In unison, they replied that they were excellent and that because the wise village leaders had them built they must be good. I suppose their respect for their elders is still alive and well, but I had hoped that kids might give a straighter answer—perhaps I am just used to American children. Later, we saw the kids playing a game of tag or hide and seek among the empty dwellings so maybe they like the homes as a playground [8].

What Went Wrong

It’s easy to sit behind a computer in your easy chair sipping Starbucks and peruse the images of McDonough’s plan and the constructed homes and declare that the reason Huangbaiyu failed was that the developers dropped an American suburb in rural China. That at least was my impression when I formulated my proposal to venture to the remote locale. If you look only at the pictures and not at the full context, this is an obvious conclusion.

The buildings appear to have garages when no residents in the village have cars and the homes seem to be a perfect model of a single-family post World War II home with a little yard for the kids to play. Yet looking at McDonough’s record, it is hard to believe that his plan would have been so ignorant of the local context. As he himself proclaims in his book Cradle to Cradle, he spent time learning about Bedouin housing on the Arabian Peninsula and working to design modern homes based on this traditional concept. Certainly an architect grounded in this spirit of merging the traditional and modern should know to incorporate the lifestyle of the residents into his plan. On the other hand, perhaps when designing for sustainability it is too easy to get caught up in considering the future and the ideal to remember to include that cultural context despite it being a vital component.

These were the thoughts swirling in my head as I rode to the village on an overnight train trying to sleep in the hard seat I occupied. It turned out that wandering through the village the next day helped me sort out some of these issues. As a note, the following couple of paragraphs are merely my own thoughts and observations and are not based on facts, articles, or interviews as the previous sections have been. As you can see from the pictures in this post, what I had seen online was true—the houses did look as advertised and recalled images of the San Fernando Valley and its rows of single-storey single-family housing. But wandering further up the road, I began to think that perhaps I hadn’t given McDonough enough credit in assessing the existing village when designing the new model. Before reading my commentary, take a look at the two pictures below. One is the yellow McDonough house and one is a current residence in Huangbaiyu.

In form at least, my initial impression was that perhaps McDonough didn’t do such a bad job after all. As you can see, in both structures the same rectangular shape is used with the elongated side facing the road and a small garage attached on the side. A boundary wall is present in both cases as well. Yet reflecting more on the two buildings and particularly their contexts, the similarities seemed to end and instead led me to question the wisdom of copying the form of the existing houses in the new development. Many architects argue that form must follow function—certainly in the context of sustainability this is true. So while certainly keeping the same form provides some sense of harmony with the existing village and a level of comfort for the residents, if the function of the houses changes, should not the form change too? I’ll explain what I mean by this in the context of Huangbaiyu.

Let’s consider each aspect of the houses’ appearance in turn and what the current function is and how it would change in the completed plan of the Model Village beginning with the elongated form. On this topic I cannot definitively say the reason for the shape, but my speculation is that it evolved as a means to harness as much daylight as possible for homes that otherwise, considering their remote location, did not have means of providing light in the daytime. This makes sense to me in context of regulations in Chinese cities mandating certain amounts of daylight in residential spaces that evolved out of ancient practices and building techniques. If this is true, maintaining this shape in the new model village would be advantageous even with solar-powered lighting simply to reduce the electrical load and therefore the necessary number and cost of solar panels. In this case, keeping the form would appear to be a good decision on the part of the architect.

Moving down the rectangle, we arrive at the storage space or garage. In the current village, I noticed some of these garages open and found that the insides revealed stores of corn and other crops that had been harvested and were waiting to be consumed, treated, or sold. As I mentioned, none of the villagers have cars, so the function of these added rooms is not as a garage as our American bias would lead us to believe on viewing these pictures. Rather I suspect they too evolved out of necessity as residents sought ways to protect their crops from the weather and pests before they were sold or eaten. In the Model Village, however, the function of individual agriculture and the need for these storehouses is substantially diminished. Considering that the original plan was to bring in industry by means of an American factory to provide jobs for those who moved into the new homes, it is unlikely that many residents would continue to farm for a living. This is especially true when considering the small plots of land surrounding the houses. For many residents, their current homes back up to their fields, so bringing crops in to store is easy and convenient. Should these same farmers live in the new village, they would have to travel great distances with their crops to store them adequately. This is for them a disincentive to live in the new homes even if they have the attached storage room. On the other hand, under the completed plan, those who chose to relocate to the Model Village and work in the factory would have storage space that presumably they now would have no need for. Perhaps there is some demand for storage I don’t know or do not anticipate, but without needing a room for keeping crops safe, what purpose could this add-on have? If none, it is an added cost in purchasing the home that could disincentivize moving into the new village.

Finally, one big difference stood out to me between the old village and the new. Even if the shapes of the houses were the same, their orientations were not. Not only were they packed more closely in the new village, they were sitting facing not the front of another house but the back of the row in front of them. On the main street through Huangbaiyu, houses sat facing across from one another in an orientation that promoted community activity and socializing. I saw a few neighbors hail one another across the way as they went to and fro. This would not be as possible in the new village. Now it could be that down the alleys in the clusters houses face each others’ backs, but out of respect for the residents whom we did not know, my companion and I did not venture down the narrow paths. However from what we could see, the clusters were networked rather than arranged in perfect rows, an arrangement which again promotes social interaction by allowing you multiple ways into and out of a location. In the new village, rows of houses meant you had to go from one end to the other to get around to your neighbor’s house even if he lived directly in front of you. This planning surprised me a bit since it seemed counter to prevailing notions of community connectedness—a key factor in sustainable cities and rural lifestyles. However, once again I hesitate to condemn this too much having only spent a day in the village and realizing that it is much easier to sit behind a keyboard and criticize than plan a village from scratch. Never having done the latter, I can’t say to what extent these issues may or may not have been considered in the planning.

In light of my observations, I began to think, could this poor planning have doomed the project? It doesn’t seem that this could have doomed it alone. After all, even if the houses did not serve the functions the farmers needed, why didn’t others move in when the new factory went up? And for that matter, why didn’t the factory go up? For answers, I again defer to the analysis and observations of Shannon May as a starting point. In an article from the “Far Eastern Economic Review,” Shannon highlights some of the reasons behind the project’s failure as a result of mismanagement by Dai Xiaolong, the principle investor chosen for his entrepreneurial and management experience. Some of these highlights include investment of over $1,000,000 of personal funds so as to dismiss the help and funding of American corporations lining up to contribute and potentially gain access to Chinese leaders as a result, dismissing the sustainability coordinator on the construction crew, ignoring safety warnings about the materials, and undersizing the central heating system (biogasification plant) leading to its abandonment [5]. For houses which were supposed to cost $3,500 each, the $1,000,000 investment certainly seems outlandish and points to mismanagement of funds. Furthermore, as Shannon notes later in the article, Mr. Dai saw the project more as an investment and even took out the rights to trademarks for a large number of sustainability and building products under the “Huangbaiyu” brand he wished to develop. Seeing it as the new synonym of sustainable, he expected to bank on the investment until he saw no return under ballooning costs and the government and CUCSD backing down. Then he turned tail and left [5].

Thinking about the mismanagement of construction while visiting the site, I crept close to the houses and, disappointed I couldn’t go inside any, looked at the quality. Remember, these were built only 5 years ago but have not had any preventative maintenance or repair. Below are images of some of the details I observed.

While the broken windows can be attribute to local hooligans, miscreants, or frustrated villagers, the thermal breaks in the insulation, peeling and cracking weatherstripping, and cracking walls cannot. Even without preventative maintenance, some of these should not yet be showing so much wear. Insulation, for instance, should not have broken down so significantly. It is unlikely that the villagers would know how to regularly inspect and upkeep window weatherstripping, so the sustainable solution would have been to use a good quality product that would not fail. Such products do exist, but not in the realm of low-end Chinese construction. In fact, the failures I saw were reminiscent in some ways of those I observed in my quickly, cheaply built superblock apartment in Shanghai. Certainly low quality was not McDonough’s intent, nor is it appropriate for a true “model village.”

Certainly a lot of the factors contributing to the downfall of Huangbaiyu can be attributed to Mr. Dai’s failure, but taking a broader stance, the question I want to attempt to address for a moment is that of how the question of success or failure could have been taken out of Mr. Dai’s hands to begin with. To do this, I want to go back to a theme I’ve harped on in the last two case studies of sustainable cities I’ve discussed (for more information, see Chapter 1 and Chapter 2). This theme is multi-level, multi-sector governance and stakeholders. As I’ve stated in my previous posts, prevailing theories in political science as applied to environmental case studies indicate that having a web of stakeholders spanning multiple governance levels and multiple sectors (private, public, residential, commercial, etc.) is one of the best ways to ensure a project’s success. On the surface, it would seem that in many ways, Huangbaiyu satisfied this criterion. It had backing from a renowned American architectural firm, Chinese government officials, Mr. Dai, a Chinese entrepreneur, and the village council through an agreement brokered with Mr. Dai. Furthermore, through the CUCSD, the project had the support of multiple American companies.

Yet if we take a bit closer look at this web, it becomes apparent that there were critical links missing to ensure the project’s success. The primary missing link was in the oversight of the project. McDonough, aside from advising and devoting time through the CUCSD, was invisible during the construction phase of the development. In America, this is a rare occurrence—typically architects are retained and maintain a stake in the project until its completion. They are often critical for clarifying decisions on the vision and mediating between reality and the client’s desires. In China, as I learned, this is not always true. Aside from architects rarely being present on-site, in China, architects can only create conceptual plans. The construction documents must be drawn up by a local design firm. Now I can’t say for sure that Huangbaiyu was subject to this regulation being a special project, but I also can’t see why it wouldn’t have been. Were it so, then Mr. Dai would have been responsible for the final drawings being completed as the construction manager and then would have also been responsible for ensuring the execution of those plans. Anyone experienced in construction in China will know that plans often get changed on-site as inexperienced workers try to make parts fit together and substitute when they feel it is appropriate to make a project cheaper, quicker, or easier for them to complete. If Mr. Dai was the manager of the project and had little construction experience, then here is the critical missing link. Without an experienced construction partner or any sort of third party review and oversight on a regular basis, the project was almost doomed from day one not to meet the vision of McDonough for an affordable, sustainable village. When independent perspectives were offered, Mr. Dai dismissed them summarily and would not listen to criticism [5]. There needed to be another voice on an even level with Mr. Dai as an investor to check the books and make joint decisions. This could have been provided by the American corporations he was supposed to court to bring a factory to the village, but despite calls for a business plan, he never produced one [5].

In addition to this missing link, another major issue was that Mr. Dai ignored the local population he was supposed to be serving. Shannon notes in the article that not once has an open-meeting been held to discuss the project [5]. Furthermore, the failure of Mr. Dai to address the factory issue that the residents required as a stipulation for the construction of the houses meant that they were never truly brought in or consulted as stakeholders in the project. They were merely used to sign off on the project and consent to using the land. A successful project must have buy-in from those who are actually going to buy. Mr. Dai adopted a Field of Dreams mentality—“if you build it they will come”—and should not have been shocked when the residents failed to materialize. But he never seemed to see from behind the dollar signs rolling in his eyes like a Donald Duck cartoon that the residents were skeptical about and didn’t even want the new village from the beginning.

Now to dismantle the last link in the project—the American component. Once again, as I said before, McDonough more or less bowed out after the design except for his involvement with the CUCSD board in San Francisco. Perhaps occupied by his 11 other city designs for China or just not given time to oversee construction in the few months in which it occurred, his absence removed the critical international component from the project. Though business leaders on multiple occasions toured the project, it was more out of respect for the CUCSD connection and in hopes that it might lead to contacts for another business deal. The CUCSD, an NGO in the US, was beholden to these investors and their whims and if none saw value in a project without a business plan, then they really had no stake in ensuring the project’s success. No matter how much the backers in the US tried to drum up interest, in the corporate environment, without Mr. Dai’s cooperation they had nothing to show investors at the end of the day and thus were paralyzed in the amount they could help.

Finally, the government support on both sides was more in principle than in financial or political oversight. Were the latter true, it is likely the project would have come under more scrutiny or been more well managed. This is a bit speculative considering that backroom deals over bai jiu (local alcohol) are reportedly rampant in smaller Chinese cities, but at the same time the authority of the government is not to be denied. China certainly saw this as a valuable marketing tool should it have been completed, but to my knowledge did not invest substantial Central Government oversight into the project.

So in the end, the web of stakeholders collapsed at the signing of an exclusive development deal with Mr. Dai. At this signing is where I believe many of these woes could have been avoided and perhaps even have written in the success of the project. In handing design development documents to a businessman with no residential contracting experience, no business plan for the factory he was beholden to produce, and no partnership with the architect or a third party consultant, the leaders of the project took a gamble on a successful distiller and lost. Had instead the deal cemented the relationships, required a business plan up front to ensure investment for future stages, and included some framework of key performance indicators (another theme of these posts) or construction management verification processes, Huangbaiyu could have been successful. Had part of the contract required regular meetings with the town, perhaps even monthly or weekly, a more open forum may have led to a different outcome. Instead, the stakeholders were brought in only when required to a minimal degree to design the plan, sign off on it and allow use of the land, or take a quick tour to try and develop business. This is not the hallmark of a sustainable business model or a city.

A Final Thought

Before I close this post, I want to leave you with one final remark—in my opinion, no matter if this project had succeeded or not, it was doomed from the start to fail in its broader mission of providing a model sustainable village. William McDonough, like other architects, no doubt understands that the idea of sustainability and the solutions therefore must be adapted in context to the location. He states as much in his TED talk when he discusses the detailed analyses his team did for the Liuzhou project [3]. Yet in China, politicians may not understand that as well. Had this project succeeded and created a completely self-sustaining, cradle to cradle village, I believe that Chinese officials would have swept in, assessed it, and then paid Chinese companies to replicate it wholesale in other parts of the nation. After all, why pay for another development fee when you can copy this design? That’s the superblock mentality and the belief that has led China to develop its own high-speed rail companies built on Siemens’ and others’ technologies. Even though McDonough was supposed to create 11 such villages, these combined would not satisfy the 400 million person urban influx China predicts to see. So the solution undoubtedly would have been to copy the model that works and then be surprised when it doesn’t work as well in another location. The concept of a “model village” is valid only insofar as you learn the process, not the product, that will lead to a sustainable town. The model to be replicated is how McDonough designed it and, had it been successful, the business model to implement it. In that way, Huangbaiyu can be considered a success in part for teaching us at least not how to implement a sustainable village. By looking at and learning from its failures, this model still can teach about the process for a sustainable village which is what it was meant to do all along.

Afterword

If you are interested in learning more about the history of Huangbaiyu, I suggest reading Shannon May’s website. You’ll find the address in link [1] below. She is the expert having lived in the village for 18 months, and her site is the most comprehensive resource I have found. I also want to stress that much of this post is based on my opinions and observations and I am happy to discuss, debate, or respond to any of the statements I have made and encourage any questions and comments below.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] http://www.shannonmay.com

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huangbaiyu

[3] http://www.ted.com/talks/lang/eng/william_mcdonough_on_cradle_to_cradle_design.html

[4] http://www.newsweek.com/2005/09/25/building-in-green.html

[5] http://www.feer.com/articles1/2007/0704/free/p057.html

[6] http://www.popsci.com/scitech/article/2007-07/chinas-green-evolution?page=1

[7] Personal Communication with Shannon May

[8] Personal Communications with residents, October 17, 2010

[9] http://www.mcdonoughpartners.com/projects/view/concept_rooftop_farming

[10] http://www.chinauscenter.org/pages/initiatives/enterprise

[11] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/5084852.stm

[12] http://www.rmhb.com.cn/chpic/htdocs/english/200609/5-2.htm

[13] http://www.openthefuture.com/wcarchive/2005/09/green_city_china.html

[14] http://e360.yale.edu/feature/chinas_grand_plans_for_eco-cities_now_lie_abandoned/2138/

[15] http://www.treehugger.com/files/2009/05/huangbaiyu-eco-village.php

[16] http://china-environmental-news.blogspot.com/2007/05/trouble-for-china-model-green-city.html